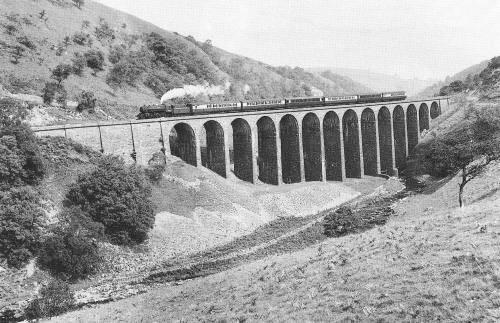

For anyone old enough to have travelled on the Stainmore Line the most enduring memories even after half a century must be of those dizzying views as the train rumbled across the high iron of the three big viaducts along the line. Each had it's own distinctive sound and special quality. From Belah in spring and autumn there were awesome views of sunsets down the Eden Valley from the the teatime train from Darlington as it steamed through windy space so far above the darkening moorland below. The dense wooded ravine of mysterious Deepdale could be come and gone in a flash as regulators were pushed full open and you skimmed along seemingly miles above the tree tops as the locomotive accelerated away from Lartington and got into its stride for the steep climb up to Bowes. And my personal favourite - Tees Valley - where suddenly pastoral views of grazing cows made way for the forested canyon of the wild peat-stained river below and you could see far down beyond Barnard Castle and to the blue line of moorlands of the 'Stang' beyond the Greta valley to the south.

For anyone old enough to have travelled on the Stainmore Line the most enduring memories even after half a century must be of those dizzying views as the train rumbled across the high iron of the three big viaducts along the line. Each had it's own distinctive sound and special quality. From Belah in spring and autumn there were awesome views of sunsets down the Eden Valley from the the teatime train from Darlington as it steamed through windy space so far above the darkening moorland below. The dense wooded ravine of mysterious Deepdale could be come and gone in a flash as regulators were pushed full open and you skimmed along seemingly miles above the tree tops as the locomotive accelerated away from Lartington and got into its stride for the steep climb up to Bowes. And my personal favourite - Tees Valley - where suddenly pastoral views of grazing cows made way for the forested canyon of the wild peat-stained river below and you could see far down beyond Barnard Castle and to the blue line of moorlands of the 'Stang' beyond the Greta valley to the south.|

The Viaducts of the South Durham and Lancashire Union Railway |

|||||

Viaduct |

Piers |

Spans |

length |

height |

|

material |

size |

||||

Lands |

masonry |

iron |

4 x 120' |

640' |

93' |

Langleydale |

stone |

stone |

11 x 30' |

411' |

76' |

Forthburn |

stone |

stone |

4 x 35' |

248' |

43' |

2 x 15' |

|||||

Percy Beck |

stone |

stone |

6 x 30' |

260' |

66' |

2 x 13' |

|||||

Tees |

stone |

iron |

5 x 120' |

732' |

132' |

stone |

2 x 21' |

||||

Deepdale |

iron |

iron |

11 x 60' |

740' |

161' |

Mousegill |

stone |

stone |

6 x 30' |

244' |

106' |

Belah |

iron |

iron |

16 x 60' |

1040' |

196' |

Hatygill |

stone |

stone |

7 x 30' |

324' |

94' |

2 x 12' |

|||||

Merrygill |

stone |

stone |

9 x 30' |

366' |

78' |

Podgill |

stone |

stone |

11 x 30' |

466' |

84' |

Smardale Gill |

stone |

stone |

14 x 30' |

553' |

90' |

Between the two big trestle viaducts on either side of the summit were 13 miles of track with only one small stone viaduct at Mousegill, just north of Barras station. Sadly in 1966 this was blown up by the army, but thanks to the local landowner the remote viaduct at Hatygill on the line down from Belah to Rookby Scarth was saved from a similar fate.

Between the two big trestle viaducts on either side of the summit were 13 miles of track with only one small stone viaduct at Mousegill, just north of Barras station. Sadly in 1966 this was blown up by the army, but thanks to the local landowner the remote viaduct at Hatygill on the line down from Belah to Rookby Scarth was saved from a similar fate.